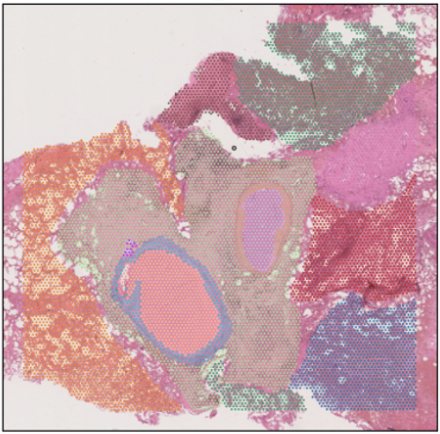

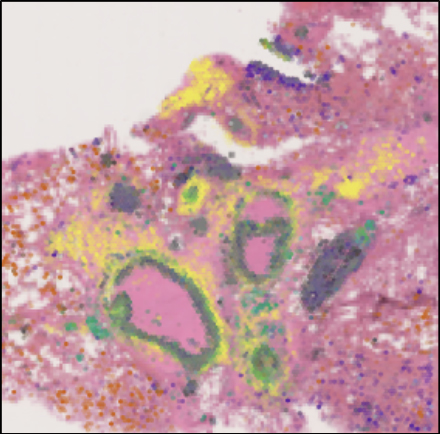

Image credit: Nana-Jane Chipampe / Wellcome Sanger Institute

Imagine being able to pinpoint exactly where in an aggressive brain tumour certain genes are turned on – like mapping a city’s most active neighbourhoods at rush hour. That is the promise of spatial transcriptomics, breakthrough technologies that are changing how scientists understand tissues, health and disease, and development.

At the Wellcome Sanger Institute, researchers are harnessing spatial transcriptomics to uncover how cells behave within their natural environments, whether in the human skin or in a parasitic worm. Collaborations across the Institute between our scientific programmes and our operational support teams are enabling us to push boundaries and continue to expand our capabilities. These collaborations lean on molecular, histological and bioinformatic expertise to generate high-resolution spatial maps of gene activity that could provide insights to transform our understanding of basic biology.

In this blog, we will take a closer look at how our Institute is applying this transformative approach, and the exciting discoveries it is making possible.

Understanding bacterial infection in cystic fibrosis patients

The first thing that many people associate spatial transcriptomics with is our ability to understand human biology. However, efforts are now being made to expand the remit of this technology to microorganisms.

Dr Josie Bryant, Group Leader in the Parasites and Microbes programme, has a focus on cystic fibrosis – an inherited disease that causes defective clearance of mucus in the lungs, making these individuals very susceptible to bacterial infections such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Mycobacterium abscessus.

Most current spatial technologies are set up for use in humans or mice. As a result, Josie’s team, including PhD student Cecilia Kyany’a have been working with Dr Kenny Roberts, Senior Staff Scientist in Cellular Operations, and the Spatial Genomics Platform team to develop their own bacterial probe panels – sets of tiny molecular ‘tags’ that can reveal bacteria – to explore the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis.

So far, they have found that both Visium – a sequencing based spatial technology – and Xenium – an imaging based spatial technology – can reveal which cells contain bacteria and where they are located in the tissue. They have seen that Xenium is a lot more sensitive for bacteria than Visium. For example, it has shown what genes the bacteria are expressing in a biofilm compared to when they are more sparsely distributed.

The team is still in the early stages of generating data and is working on adapting a lot of the existing downstream bioinformatic pipelines – which again are designed primarily for human samples. One of the biggest challenges is the fact that bacteria are a lot smaller than human cells and they do not have nuclei. This makes it difficult to distinguish individual cells with this technology at the moment; they can currently only see where a population of bacteria are located.

“For me personally, it's amazing because so much of what we do in microbiology when we're looking at host-pathogen interactions, is we'll take the bacteria, and we'll grow it in the lab. Then, we'll come up with an idea, for example, ‘neutrophils are important in this type of bacterial infection’, and then we'll grow them together and see what happens. And that's great, we've learned a huge amount from that kind of approach. But we're not seeing it directly from the patient. So, it's amazing for me to see all these host-pathogen interactions playing out in tissue from the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis. We're seeing it in the real world for the first time rather than through experimentation. That's what I find really exciting about this technology; it removes all the inferences that we have to make in the lab when we're doing these experiments – now we can just directly observe it.”

Dr Josie Bryant,

Group Leader, Wellcome Sanger Institute

For chronic diseases, patients often end up with infections from multiple pathogens and it is hard to determine when to treat and which bacteria to focus on. Also, for many patients with chronic diseases, they often end up with lots of damaged tissue making them even more susceptible to other infections down the line. Josie hopes that with this type of work we can understand which specific tissues are being damaged by particular bacteria, so we have a better idea of what we need to target.

Looking at the somatic mutation landscape in lung diseases

As part of a collaboration between Dr Peter Campbell’s, Former Head of the Cancer, Ageing and Somatic Mutation programme – now Somatic Genomics – and Dr Josie Bryant’s groups, Dr Chuling Ding, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, is working to characterise the distribution of bacterial colonisation in patients with cystic fibrosis. While Josie is focusing on the bacterial side, Chuling is planning to focus more on human tissue. She is studying the somatic mutation landscape – the DNA changes that cells acquire during a person’s lifetime – in cystic fibrosis and characterising whether the distribution of bacteria colonisation correlates with somatic mutations.

Chuling will be combining Xenium data with laser capture microdissection (LCM) to explore the interplay between humans, the mutational landscape and the infectious microorganisms. LCM is a technique that uses a laser to precisely cut around specific groups of cells, which then undergo further downstream sequencing. It provides information based on DNA samples, which enables you to gain information on somatic mutations. This can then be combined with information from RNA samples using spatial – both of which are from the same location.

With support from Dr Kenny Roberts, this will be the first time Xenium is being used on PAXgene fixed human tissues. PAXgene is an approach that ensures the preservation of RNA or DNA within blood samples, which is important when wanting to study somatic mutations. As PAXgene is commonly used in the Somatic Genomics programme, Kenny has been working to optimise protocols from scratch to try and get Xenium to work, broadening the applicability of spatial transcriptomics.

The hope is that this work will enable the researchers to understand the interplay between infection and somatic mutations when chronic infection begins. This could identify new targets for treatments in the future and improve patient prognosis.

“Our work on cystic fibrosis provides an example of how the airway cells adapt under selective pressures driven by the condition. By leveraging the advances of spatial transcriptomics, we now have unprecedented resolution to learn the changes in cells or tissues that happen because of these DNA mutations and how they affect infections and disease progression. We hope this study will bring us new insights to better manage the disease and bring potentially new opportunities for therapeutic options.”

Chuling Ding,

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Wellcome Sanger Institute

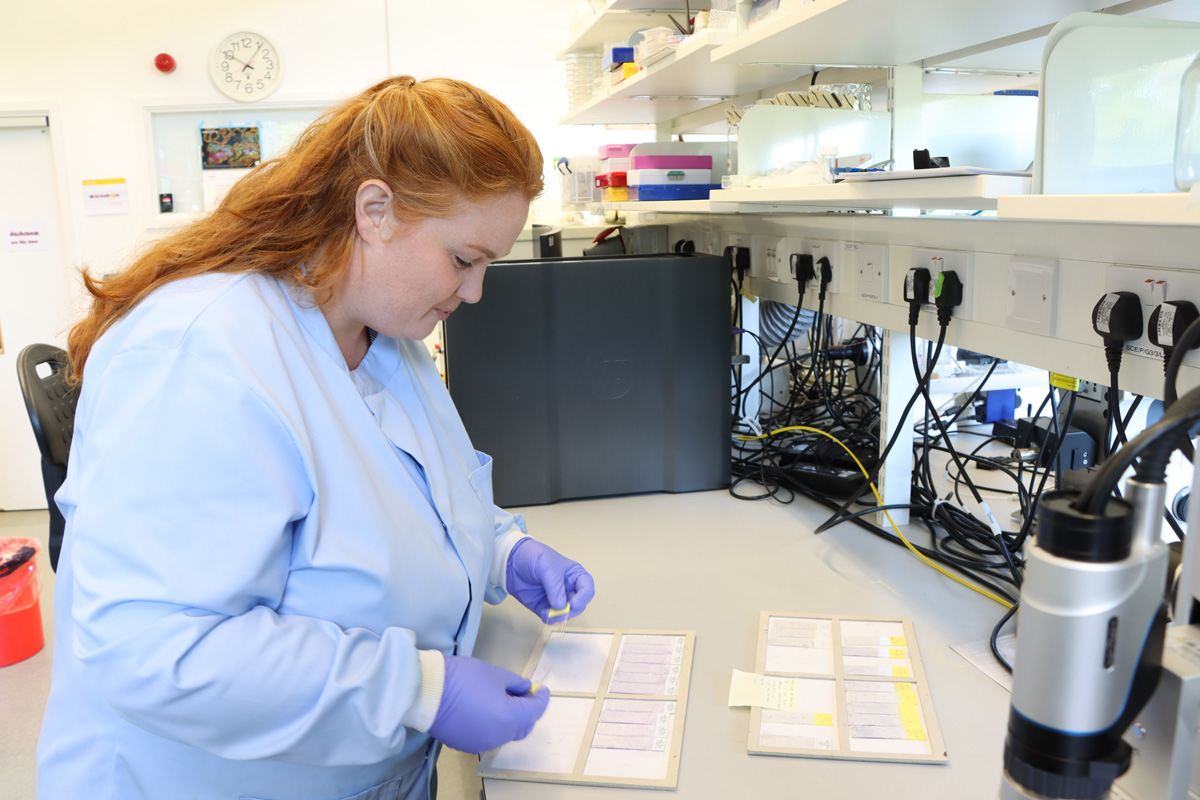

Applying spatial techniques to parasitic worms

Another area where spatial is being adapted is to study parasitic worms. In 2024, Dr Sarah Buddenborg, former Postdoctoral Fellow in Dr Steve Doyle’s group, won a Sanger Accelerator Award to fund her research on characterising the development and disease stages of parasitic worms – helminths – that infect humans and animals. It is estimated that 1.5 billion people are living with soil-transmitted helminth infections.1

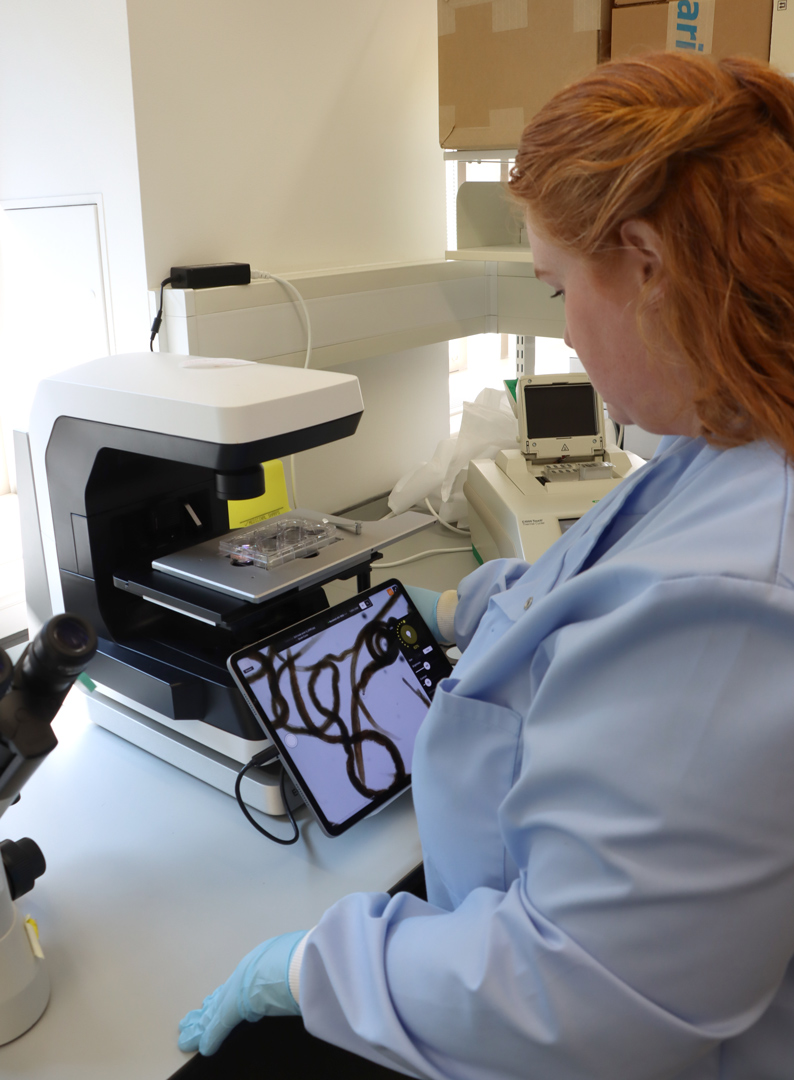

Sarah was working primarily on Haemonchus contortus, also known as barber’s pole worm, a nematode that infects small ruminants – sheep and goats primarily. It causes large flocks to become very ill, and many can die. Other related worms also cause infections in humans.

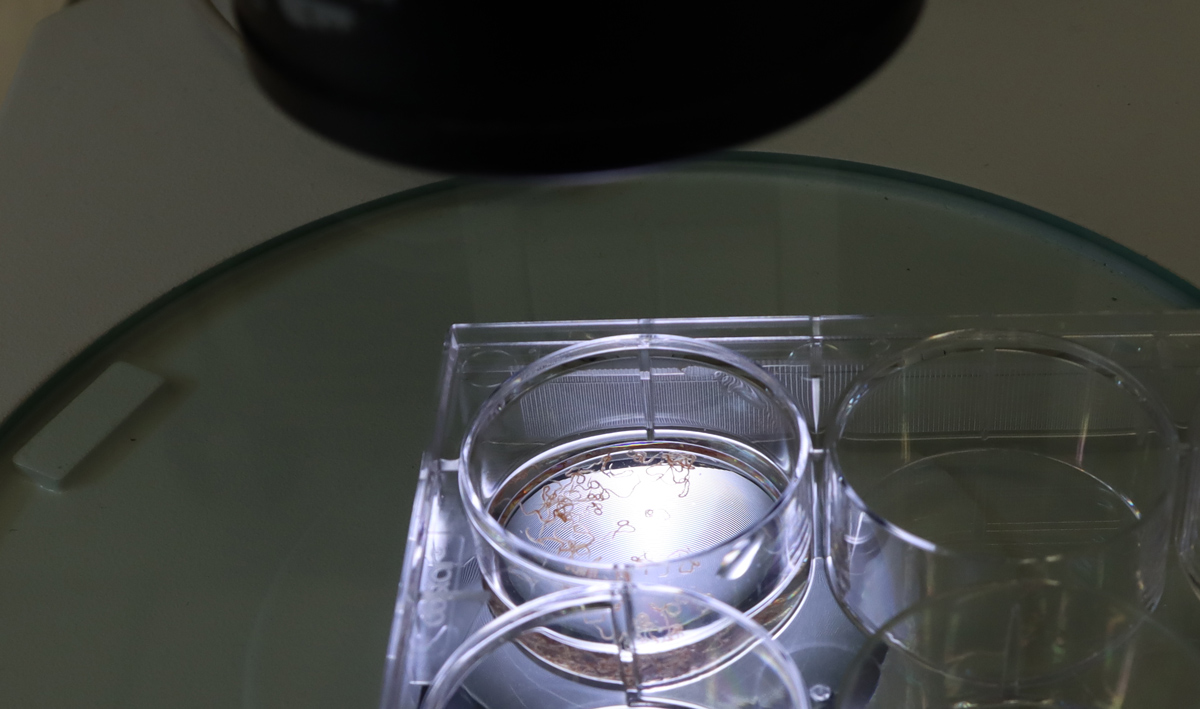

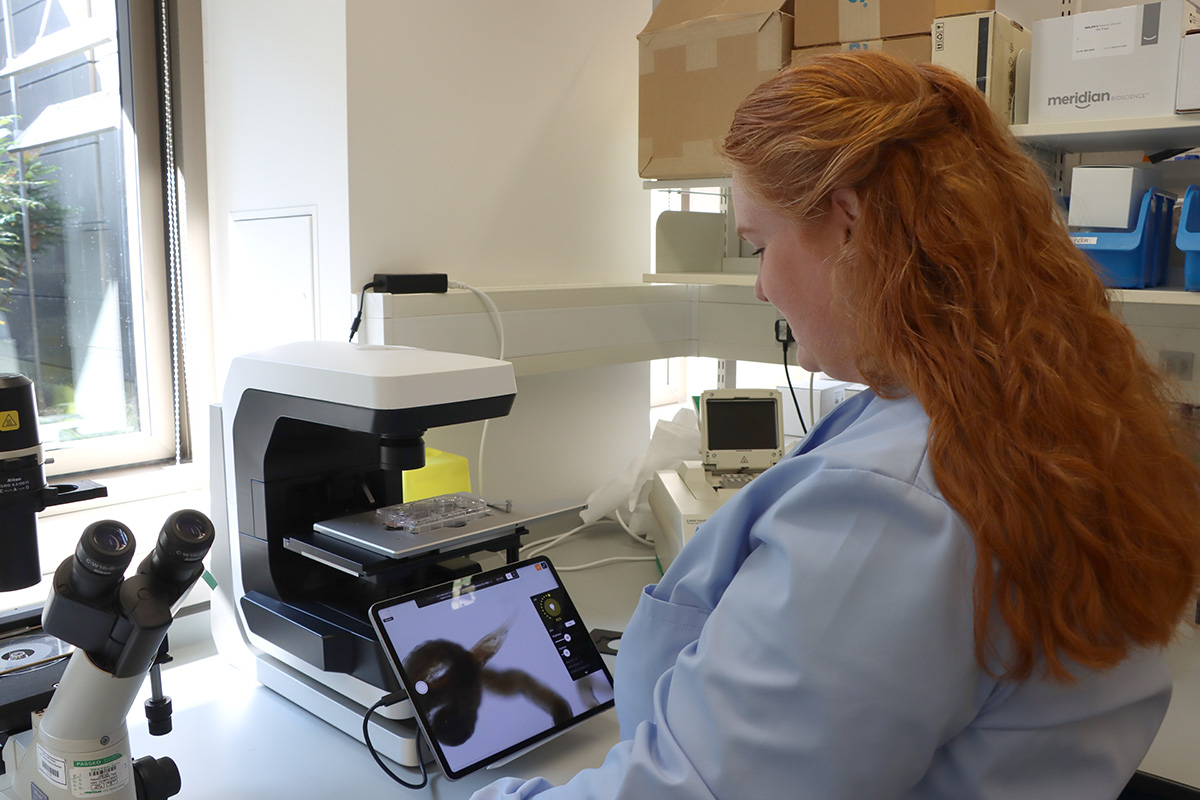

Spatial technology previously could not be used on worms before because the spots on the slides – the tiny areas that detect molecules in cells – were too far apart. When the spots are closer together, the technology can capture more detail, giving a clearer picture of what each cell is doing. In human tissue, cells of the same type often cluster together, so not seeing individual cells is not as big of a problem – neighbouring cells usually behave the same way. But in tiny worms, very different cells can sit right next to each other. With the original spatial technology, you would not have been able to tell what each cell type was doing or distinguish between them.

In the last few years, new technologies have emerged that allow large scale, high-throughput spatial at greater resolution. Now, you can have probes right next to each other. As part of their work, Sarah was using the spatial technology Curio on these worms for the first time. Curio slides are typically 3 millimetres by 3 millimetres and these worms are approximately 500 microns by 25 centimetres. Most of the drug resistance and susceptibility targets are in the neurons located in the head of these worms. Therefore, Sarah was taking the first 3 millimetres and packing loads of them in one slide.

The first sets of experiments were proof of concept to understand what results they could get back and to optimise their experiments. In the long-term, Steve’s group hope to do the whole worm, identifying what cells are present, what genes are active and how a resistant worm compares to a worm that is susceptible to treatments. Most of our current knowledge of these worms comes from drawings from the 1800s – this technology will hopefully produce high-resolution images that can provide us with basic information like we have for mammalian tissues.

In the future, the team hopes to also expand this work to a more diverse species of worms that infect both humans and non-humans. This will hopefully provide insights into how to better control these infections.

“Adapting spatial transcriptomics to organisms like parasitic worms allows us the opportunity to uncover novel biology of these amazing but devastating organisms at a scale not previously possible.”

Sarah Buddenborg,

Former Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

Delving into the skin and associated inflammatory disorders

Spatial omics is providing unprecedented information on human tissue ecosystems. In 2024, Head of the Cellular Genomics programme and Deputy Director of the Institute, Professor Muzz Haniffa’s team released a prenatal skin atlas. This characterised the cellular composition of developing human skin at single cell resolution, as part of the Human Cell Atlas. The Human Cell Atlas aims to create maps of all human cells to help understand human health and disease. This first prenatal skin atlas was mainly built using single cell data and highlighted the immune and non-immune cell crosstalk contributing to skin development. The team is now working to expand this skin development research by incorporating much more spatial data and expanding sampling across anatomical regions to understand how different types of skin are made. For example, scalp skin produces lots of hair, and palm skin, which is thicker, does not.

“We have defined most of the cell types that make up the human body through the Human Cell Atlas initiative. The next phase will be leveraging spatial omics to enable us to understand how these cells assemble into functional units – akin to how a set of bricks come together to form different houses.”

Professor Muzlifah Haniffa,

Head of the Cellular Genomics programme and Deputy Director of the Wellcome Sanger Institute

As part of this work, the team hopes to understand more about the developmental processes involved in hair follicle formation. Hair follicles are tiny, multicellular structures in the skin from which a hair fibre grows, and all the hair follicles we have on our bodies are established in the embryo before we are born. Our current understanding of the developmental stages of the hair follicle has largely come from work in mice. Now, for the first time, Muzz’s team is mapping the molecular landscape of human hair follicle development at a subcellular resolution. The team has generated a new dataset of the prenatal scalp skin using samples from the Human Developmental Biology Resource.

As hair follicles are very tiny structures within the skin, their constituent cells can be hard to isolate in single cell sequencing experiments – where the tissue is broken down to separate the cells out. Spatial technologies provide an alternative, increasing our resolution of these cells and allowing us to see them in the context of whole tissue.

This work, led by Senior Staff Scientist Dr April Foster, will use spatial technologies to explore how the cells are organised and what genes these cells express during hair follicle development. The team is using a predesigned 5,000 gene panel but has also added 100 other genes, which they know are important in developmental biology from existing literature. Their initial findings include the transcriptomic profile of the developing sebaceous glands – these are structures that secrete sebum (a natural oil substance) into the hair follicle.

The team hopes that by understanding what initiates hair formation and mapping how it happens, we may be able to reverse the effects that are seen with conditions like alopecia or balding in the future.

If we can understand these developmental pathways in embryos, we might also be able to understand how things go wrong in skin cancer. To address this, Muzz’s team is also collaborating with Senior Group Leader and Interim Head of the Somatic Genomics programme, Dr Dave Adams’ team to profile skin cancers that arise directly from the hair follicle region.

On top of delving specifically into the hair follicle, Muzz’s team has also generated an inflammatory skin atlas including single cell datasets across 22 different skin diseases including psoriasis, eczema, hidradenitis suppurativa (causes recurring lumps) and skin cancers. This new atlas has already uncovered what characteristics are retained across inflamed skin, and the team will now be using spatial technologies to map cell organisation in the skin of psoriasis and eczema patients. So far, the team has identified novel ‘hidden’ tissue niches in inflamed skin, including tissue resident immune cells called memory T-cells as well as other supporting factors.

“Spatial omics is providing unprecedented information on the skin and all the other tissue ecosystems that make a functioning human body. This information allows us to ‘decode’ how these ecosystems work, and then ‘recode’ them using in vitro systems, with a lot of help from AI. It’s an incredibly exciting time to be doing science here at the Sanger Institute.”

Professor Muzlifah Haniffa,

Head of the Cellular Genomics programme and Deputy Director of the Wellcome Sanger Institute

Building a holistic atlas of glioblastoma

Glioblastoma is the most aggressive adult brain tumour as well as one of the most studied solid tumours. For the past 20 years, researchers have thrown the entire arsenal of molecular tools at these tumours but despite these efforts, the needle has not moved for patients. Over 75 per cent of patients will die within the first year of diagnosis.2 In addition, treatments have barely changed, with the first line of standard treatment being the same since 2005.

In order to develop new drugs to treat glioblastoma, we have to understand these tumours in patients themselves, rather than relying solely on cell lines and animal models, thereby enabling deeper insight into their fundamental biology. Over the past few years, with funding from Wellcome LEAP, Dr Omer Bayraktar, Group Leader in the Cellular Genomics programme, has been leading work on building the deepest multi-modal glioblastoma cell atlas. The idea of this project was to leverage all the different technologies available, including single cell and spatial omics, and put these together using computational tools to take a holistic look at the biology of these tumours.

While their findings are yet to be published, the team found that the different cancer cell states in these tumours have a very particular spatial organisation. Their work explores potential cellular trajectories – how cancer cells may transition between states – and how these transitions could influence tumour architecture. They anticipate that their discoveries will lay the groundwork for exploring more complex questions, such as uncovering the differences between these tumours. Looking ahead, they hope that their findings could eventually be harnessed as a therapeutic strategy.

“We have learned that there is tremendous potential to understand and really unlock the complex disease biology in patient tissues using these methods. We are now very convinced that you need the combination of different atlasing technologies and the spatial resolution, but you also need the computational tools that allow you to integrate them and make sense of these data.”

Omer Bayraktar,

Group Leader, Wellcome Sanger Institute

Profiling granulomas in the lungs of patients with tuberculosis

With separate funding from Wellcome LEAP, Dr Omer Bayraktar’s team has also established a collaboration with researchers at the Africa Health Research Institute in South Africa to study lung granulomas – an area of tightly packed immune and diseased lung cells in individuals infected with tuberculosis (TB).

This work, led by Senior Staff Scientist Dr Fani Memi, uses spatial technology to profile granulomas and the surrounding lung tissue changes that cause functional impairment, in order to understand and predict transitions between different TB disease states. To date, we still do not understand what determines whether granulomas resolve, progress or disseminate; therefore, this work will shed more light on the evolution of granulomas and our overall understanding of disease progression.

One of the initial challenges the team has faced is in relation to the samples. The tissue they received for the project was quite old and had not been optimally prepared and stored for spatial – most spatial technologies work best with fresh frozen tissue, whereas these tissues had been stored in formalin for many years. Despite this challenge, Fani and the team ran several pilot tests to optimise the protocol and eventually were able to detect TB genes for the first time, as well as increase overall sensitivity of gene detection.

The team will now be focussed on providing spatial and data analysis expertise to their collaborators, who will harness their knowledge on the bacterium to generate insights that could transform our understanding of these tissue structures.

The team’s initial results point at a surprising degree of spatial organisation in the granulomas. Currently, Fani and the team are trying to see if granuloma spatial architecture changes across different stages of tuberculosis infection.

A particular interest of the teams is the intriguing similarities between tumours and granulomas in the way they manipulate the immune system to their benefit. Comparing their respective spatially complex cellular microenvironments might reveal common principles of chronic tissue responses and immune-pathogen/immune-tumour interactions.

“What makes this project unique is the rare opportunity to study the entire clinical continuum of tuberculosis including active, latent, subclinical and healed disease. This is possible thanks to an exceptional collection of post-mortem and surgical resection samples of granulomas, contributed by our collaborators. The cohort is multiethnic and includes both HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals, as well as drug-resistant and drug-susceptible cases, drawn from a high-incidence setting. Together, these samples show the full range of changes the disease can cause in the tissue which may mirror how the illness progresses. Mapping the transcriptional signatures of the different lesions and the cellular crosstalk in play will provide new insights into the molecular pathways involved in the transitions between the disease states and hopefully provide new therapeutic avenues.”

Fani Memi,

Senior Staff Scientist, Wellcome Sanger Institute

Investigating how Down syndrome alters brain development

Down syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, is a rare genetic disorder caused by an extra full or partial copy of chromosome 21. While individuals living with Down syndrome lead fulfilling lives and their life expectancy has dramatically increased in recent decades, many still suffer from significant health problems including congenital heart disease, vision and hearing loss, increased risk of infection and thyroid problems. They also show varying degrees of cognitive delays, from very mild to severe, and can develop dementia at an earlier age.

The extra chromosome also impacts brain development, resulting in smaller brain size and altered brain structure. To delve further into this, Dr Omer Bayraktar and his team are using spatial technologies to explore how trisomy 21 influences brain architecture and gene expression in developing brains. These samples were donated to Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge and shared with the Bayraktar lab at Sanger.

The team first used single cell genomics to create a reference cell atlas and then mapped these cell types into their tissue locations using spatial transcriptomics. They then compared their findings to non-trisomy brains. So far, they have found differences in the abundance of different cell types and gene expression, and observed unexpected changes in the architecture of certain brain areas. Their initial findings suggest more widespread cellular changes in Down syndrome than previously thought. The team wants to follow-up these findings with functional experiments to gain deeper insights into the differences.

“The development of the human brain and the ways it differs in people with Down syndrome is remarkably complex. We are excited to use the discovery power of single-cell and spatial transcriptomic technologies to explore these intricacies in a careful and respectful way. Our hope is that this work will deepen our understanding of early brain development in Down syndrome and help lay the groundwork for future therapeutic insights.”

Fani Memi,

Senior Staff Scientist, Wellcome Sanger Institute

Mapping the activity of autism-associated genes across brain development

Autism is an incredibly complex and heritable neurodevelopmental condition with a wide range of characteristics. Over 20 per cent of individuals with autism have limited spoken language, co-occurring epilepsy, intellectual disability and other significant challenges, and require high levels of everyday support.3 This presentation is often referred to as profound autism. We know from three decades of research that rare, protein-disrupting variants in roughly 300 genes are strongly associated with this form of autism. In order to understand how these genes impact brain development, the next challenge is to identify which regions of the brain these genes are expressed in.

Until recently, our understanding was that these autism-associated genes affected the cerebral cortex – part of the human brain that is thought to underlie our cognition, emotion, complex behaviour and other functions. Combined with the fact that the cerebral cortex is one of the most accessible areas experimentally, over the years the majority of research on autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders has focussed on this region of the brain.

As part of work funded by the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI), Dr Omer Bayraktar and his team have leveraged spatial technologies to map where autism-associated genes are most highly expressed during human brain development. More specifically, they have looked at 250 of the 300 previously identified autism-associated genes alongside 65 cell type markers that label different developing brain cell types. Using samples received from the Human Development Biology Resource (HDBR), the team examined the patterns of gene activity across the developing brain beyond just the cerebral cortex. Although these findings have not yet been published, they hope that their work will shed light on early developmental processes that may be relevant to profound autism.

“Globally, there is significant effort to understand the mechanisms of autism-associated genes, often using models focussed on the cerebral cortex. Our work investigates how different brain regions may contribute to features of profound autism. Over the next 10 to 20 years, mechanistic insights into how these autism-associated genes function in other brain regions – outside of the cerebral cortex – may not only deepen our understanding of autism, but also provide broader insights into other neurodevelopmental conditions.”

Omer Bayraktar,

Group Leader, Wellcome Sanger Institute

References

- World Health Organization. Soil-transmitted helminth infections. January 2023 [Last accessed: January 2026].

- The Brain Tumour Charity. Glioblastoma Prognosis. [Last accessed: January 2026]

- Hughes MM, Shaw KA, DiRienzo M, et al. The prevalence and characteristics of children with profound autism, 15 sites, United States, 2000-2016. Public Health Reports. 2023; 138: 971–980. doi: 10.1177/00333549231163551

Header image

Representative image of a large airway with extensive inflammation, possible early stage granulomas, mucus and debris. 17-plex Immuno-Oncology biomarkers of alveolar airways from Cystic Fibrosis lung tissue, acquired on the RareCyte Orion Spatial Biology platform.