Image credit: CDC/ PHIL and Adobestock

Ten ways the Sanger Institute is tackling the global fight against AMR

By Shannon Gunn, Senior Science Writer at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has been a buzzword for decades. It refers to when antimicrobial medicines are no longer effective against bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites. These infamous ‘superbugs’ that harbour resistance genes have been, and continue to be, a topic of conversation across the research community and the media due to the difficulty in treating them and increased risk of transmission.

Don't miss out

Sign up for our monthly email update

In 2019, it was estimated that bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was directly responsible for 1.27 million global deaths.1 Researchers predict that this figure could increase to 1.91 million by 2050 if action is not taken.1 In 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) called for global leaders to work together to reduce these deaths by 10 per cent by 2030.2

In support of this goal, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute are using advanced genomic technologies to analyse the AMR landscape of several different microorganisms. As the effects of AMR disproportionately affect under-resourced countries, our teams are also working with collaborators around the world to support sequencing and build capacity directly within affected countries.

In our latest blog, we delve into ten ways that researchers at the Sanger Institute are working with collaborators to help accelerate action against AMR around the world.

1. Strengthening global genomics capacity for AMR surveillance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) affects all countries. However, the drivers and consequences of AMR are exacerbated by lack of resources, meaning low- and middle-income countries are most affected. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, nearly 1 in 1,000 deaths are associated with bacterial AMR.3 This is compared to half as many in high-income countries.3

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) affects all countries. However, the drivers and consequences of AMR are exacerbated by lack of resources, meaning low- and middle-income countries are most affected. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, nearly 1 in 1,000 deaths are associated with bacterial AMR.3 This is compared to half as many in high-income countries.3

To address this disparity, it is important to target AMR at the community level by enabling the sequencing and analysis of AMR data directly within country settings.

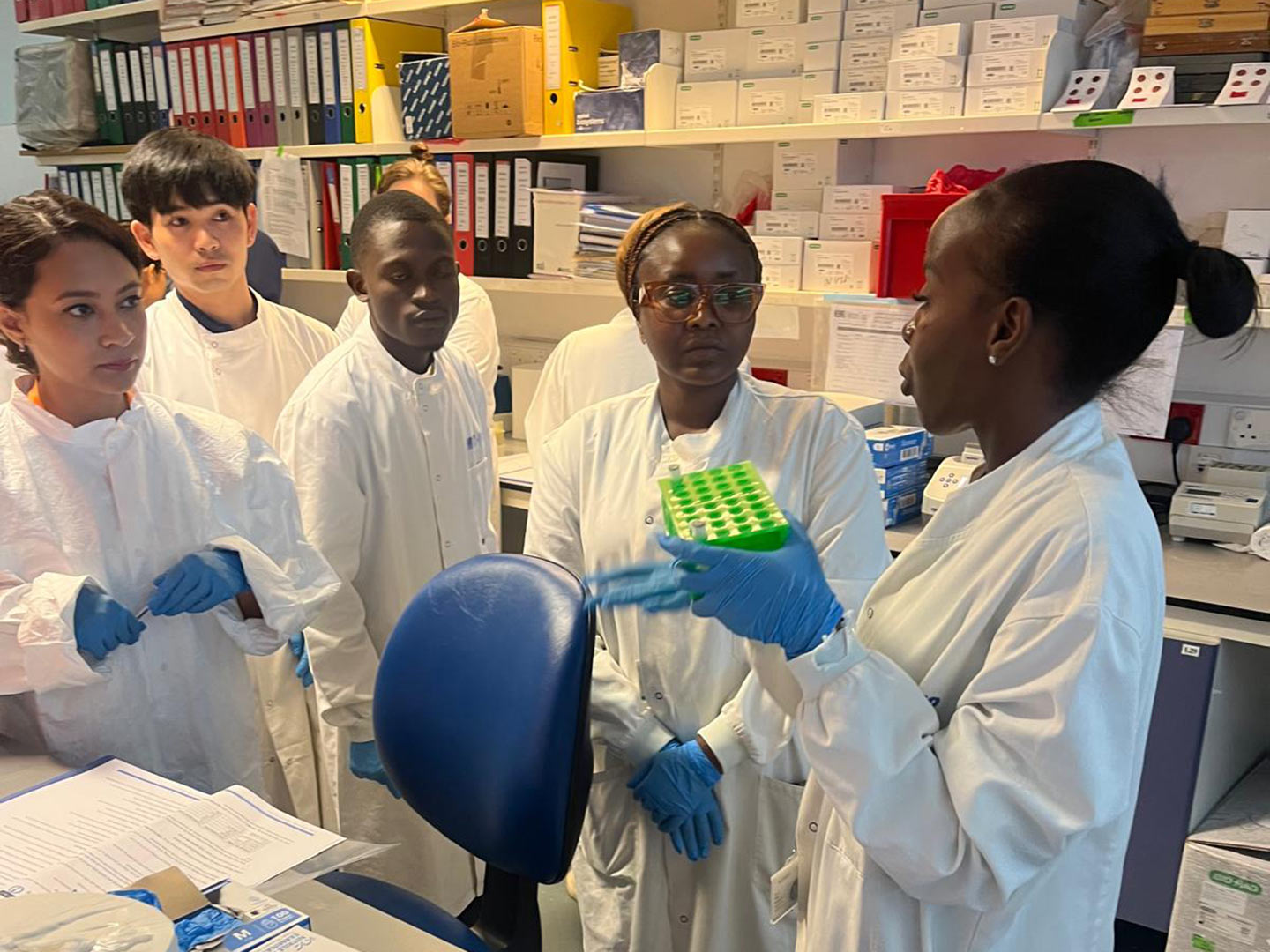

Wellcome Connecting Science at the Sanger Institute is running learning and training activities in the UK and globally to empower scientists worldwide and improve AMR surveillance. These activities cover four key areas:

- Training courses: These courses enable participants to get access to advanced genomics tools and technologies that could be applied to their own work. These programmes can be comprehensive in-person events, such as the ‘AMR in Bacterial Pathogens’ course alternating between Africa and Asia, including the 2023 training in Mahidol University in Thailand. They can also be more foundational online courses, such as ‘Antimicrobial Databases and Genotype Prediction: Data Sharing and Analysis’, which provides scientists at all levels with the resources and tools to navigate genomic data to understand AMR.

- Communities of practice and peer networks: Creating opportunities for peer networks and communities of practice is essential for sustained engagement, knowledge exchange and addressing shared challenges in AMR. The Connecting Science team recently hosted their first symposium for African scientists engaged in AMR work, bringing together participants from 20 African countries, many of whom had previously taken part in Connecting Science’s various training courses. The symposium focused on exploring the real-world application of their skills in genomic surveillance of AMR. Building on the foundations of the SAGESA (Society for African Genomic Surveillance of AMR) peer network, participants outlined clear goals and objectives for a sustainable community of practice, reinforcing their commitment to continued collaboration and impact in the field of AMR using genomics.

Conferences and training courses run by Wellcome Connecting Science in partnership with the Sanger Institute. Image credits: Ben McDade Photography and Mark Danson / Wellcome Connecting Science.

- Knowledge sharing: Forums for multidisciplinary AMR experts to convene are critical for shaping an equitable global surveillance infrastructure. The Connecting Science ‘Antimicrobial Resistance – Genomes, Big Data and Emerging Technologies’ biannual conference, held in the UK, provides an open and inclusive learning environment for researchers to share the latest data insights and global health challenges, explore new genomics tools and technologies, and ultimately define priorities for developing better data sharing capabilities across borders. The next conference is being held between the 23rd and 25th March 2026. You can register your interest here.

- Collaborations: Working with partners is key to ensuring diversity of experience and shared insights. A recent AMR training course, delivered as part of the ACORN (A Clinically Oriented antimicrobial Resistance Network) project, was co-developed with regional partners to address existing genomic skills gaps and expertise across countries in Africa and Asia. The collaboration focused on equipping project researchers and healthcare scientists with the tools to integrate genomics into routine hospital care, while considering contextual implementation challenges. These tailored courses are designed to support health institutions, respond to community needs and overcome local barriers to effective AMR surveillance.

“Tackling the AMR challenge through genomics requires more than a one-size-fits-all approach. At Wellcome Connecting Science, we are responding to this global issue through targeted, multifaceted approaches that reflect the complexity of needs across different contexts. By enabling inclusive and collaborative communities, we are contributing to a collective global response and driving lasting impact.”

Alice Matimba,

Head of Training and Global Capacity, Wellcome Connecting Science

2. Changing policy for syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum. Symptoms can be mild and sometimes go unnoticed, making it challenging to diagnose and leading to further transmission. If untreated, syphilis can lead to serious, potentially life-threatening complications, damaging the heart, brain and other organs.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum. Symptoms can be mild and sometimes go unnoticed, making it challenging to diagnose and leading to further transmission. If untreated, syphilis can lead to serious, potentially life-threatening complications, damaging the heart, brain and other organs.

In 2022, it was estimated that 8 million adults between the ages of 15 and 49 acquired syphilis.4 While syphilis can be treated with first-line antibiotics, such as benzathine penicillin, emerging antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is still a growing concern. In particular, in the UK, approximately 94 per cent of syphilis strains are resistant to azithromycin.5 In the US, it is nearly 100 per cent.6 Interestingly, however, ongoing research at the Institute indicates that in some African countries, its percentage is significantly lower. This means that in some countries you cannot use azithromycin at all, and in others the drug can still be prescribed.

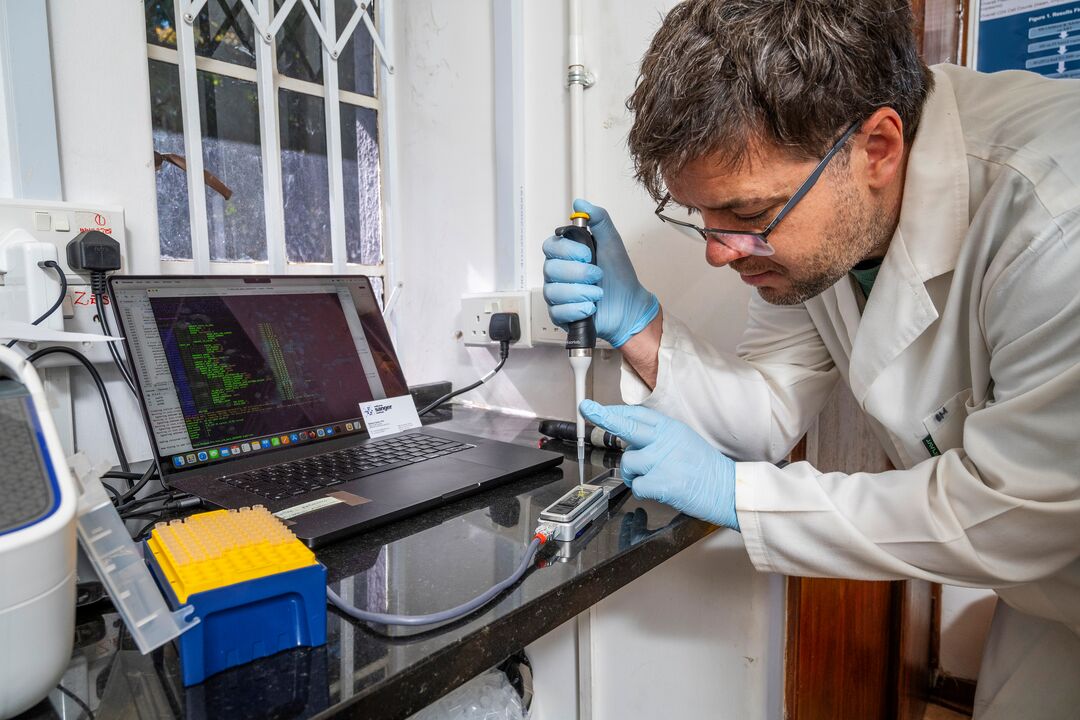

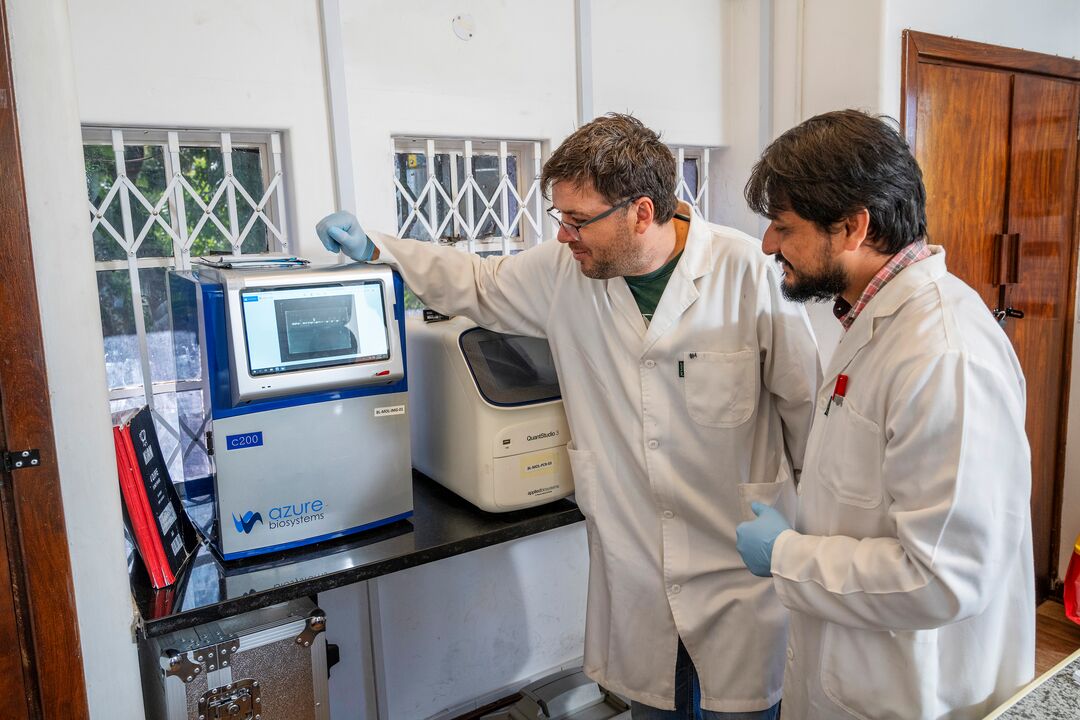

At the Sanger Institute, Dr Mathew Beale, Senior Staff Scientist in Professor Nick Thomson’s group, and colleagues are using whole genome sequencing to understand how AMR evolves and spreads and how it is associated with particular lineages. From ongoing analyses, they have found that drug resistance is being brought into Africa from countries outside of the continent, which ultimately impacts treatment programmes due to the different strains present.

Mat Beale (in both photos) and Vignesh Shetty from Professor Nick Thomson's research group travelled to Zimbabwe to work with collaborators at the Biomedical Research and Training Institute (BRTI) to carry out research and training. Image credits: Chris Scott / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Mat and his colleagues’ ongoing work has emphasised the power of genomics in both research and public health. Their research continues to play a role in developing our understanding of the biology of syphilis and has also been cited in changes to the UK and European treatment guidelines, which now no longer recommend azithromycin.

“Genomics has enabled us to understand that lineages are associated with resistance, which is something we didn't know before. We thought we saw resistance rates rising, but we didn't realise that this was associated with particular lineages and transmission networks. Now, we can see that this is the case because genomics has allowed us to pull that apart.”

Mathew Beale,

Senior Staff Scientist, Parasites and Microbes programme

3. Analysing AMR evolution in Yaws

While one subspecies of Treponema pallidum causes syphilis, another causes a different condition called yaws. Yaws, caused by the subspecies pertenue, is a neglected tropical disease (NTD) primarily affecting young children. It impacts the skin, bones and cartilage and causes disfiguring lesions. It is transmitted by skin-to-skin contact via cuts. There are currently 16 countries known to be endemic for yaws, including Liberia and Ghana.7

While one subspecies of Treponema pallidum causes syphilis, another causes a different condition called yaws. Yaws, caused by the subspecies pertenue, is a neglected tropical disease (NTD) primarily affecting young children. It impacts the skin, bones and cartilage and causes disfiguring lesions. It is transmitted by skin-to-skin contact via cuts. There are currently 16 countries known to be endemic for yaws, including Liberia and Ghana.7

As part of WHO’s NTD road map, yaws has been targeted for global eradication by 2030. Their eradication strategy involves mass drug administration (MDA) of single-dose oral azithromycin. This drug was selected as there has been very little documented drug resistance to it until recently.

Yaws nodules, caused by the Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue. Image credit: Dr Peter Perine / CDC PHIL.

Alongside their work in syphilis, scientists in Professor Nick Thomson’s research group are also exploring the effects of such eradication efforts on the evolution of the bacterial population behind yaws. They are demonstrating how molecular and genomic epidemiology approaches can be used to inform these efforts moving forward.

As part of this research, Dr Amber Barton, Sanger Epidemiological and Evolutionary Dynamics (SEED) Postdoctoral Fellow, led a recent piece of work that explored the impact of MDA of azithromycin on the dynamics of yaws transmission in the Namatanai District of the Island of New Ireland, Papua New Guinea. They found that MDA was successful in reducing and maintaining the genetic diversity of yaws at a low level. They also saw that yaws was not spreading; people who lived closer together shared closely related strains. The two predominant strains at the end of the study had mutations in penicillin-binding proteins, which have also been found in syphilis. These findings could help inform future elimination strategies and are set to be published later this year.

“The emergence of macrolide resistance in yaws throws up a conundrum – whether it is better to throw everything you have at it and hope to completely eliminate it before resistance becomes widespread or take a more cautious targeted approach to try and prevent resistance becoming widespread in the first place. It is really exciting that we find that even on a small island, yaws does not seem to spread far. It has shown us that targeting small geographic areas or schools could be a feasible strategy.”

Amber Barton,

SEED Postdoctoral Fellow, Parasites and Microbes programme

4. Optimising culture techniques to uncover more about Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is the world’s leading cause of death from a single infectious agent.8 In 2023, over 10 million people worldwide fell ill with TB with 1.25 million dying.8 Multi-drug-resistant TB remains a public health concern, with only two in five individuals with drug-resistant TB accessing treatment in 2023.8

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is the world’s leading cause of death from a single infectious agent.8 In 2023, over 10 million people worldwide fell ill with TB with 1.25 million dying.8 Multi-drug-resistant TB remains a public health concern, with only two in five individuals with drug-resistant TB accessing treatment in 2023.8

Diagnosing TB is difficult due to a variety of factors including varied symptoms, difficulties in obtaining good quality samples and limited availability of diagnostic tools in resource-constrained countries. In 2023, it was estimated that around 38 per cent of patients diagnosed with TB worldwide were not microbiologically confirmed.9 This knowledge gap makes trying to understand transmission networks a challenge. In addition, to get genomic information or to test for drug resistance, samples need to be cultured in a Containment Level 3 (CL3) lab. This involves extensive safety requirements, trained personnel and a lot of resources – all of which make it expensive to run. TB predominantly affects low- and middle-income countries where there are often less resources, making this approach inaccessible to many.

Dr Belén Saavedra, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Dr Josie Bryant’s team at the Sanger Institute, is working to optimise culture-free sequencing methods to gain deeper insights into TB and make this work more accessible. Belén’s project is using samples from a previous population-based study that took place over one year in Mozambique. The team worked alongside The Mozambican National Tuberculosis Control Programme to diagnose new patients and obtain samples from their family and close community contacts. From 1,000 TB patients diagnosed through the national programme, they screened around 7,900 people and found 90 more cases of TB. Although they successfully cultured samples and identified 321 strains of M. tuberculosis, bacteriological confirmation rates were relatively low – only 37 per cent among the initial cases and 53 per cent among contact cases.

Belén at work in her lab. Image credit: Shannon Gunn / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Now, as part of her fellowship at Sanger, Belén is trying to collect more information from these respiratory samples by optimising protocols for culture-free sequencing. She has approximately 400 samples that previously produced negative results through current available diagnostic tests. Belén is applying different research techniques that have been explored by her colleagues for other respiratory diseases and seeing if they work for M. tuberculosis. She has just run a mock experiment using sputum with no pathogens, and mixed it with different quantities of M. bovis, which is closely related to M. tuberculosis. She treated those samples with different protocols, and has just sent them for sequencing, so is waiting for the results.

After she has identified a suitable protocol, Belén will go back to the samples in the freezer and test them. The hope is to identify more strains and fill in the missing data gaps from the TB transmission network that they identified with the initial samples.

This work will also be important for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as if experts can sequence samples directly from the patients after sample collection, they can then look for drug-resistant markers within a few days. This will allow them to start treating patients in the right way and at the right time, reducing future spread.

While some TB strains respond to therapies, treatment programmes can be long and are often associated with side effects, meaning sometimes people stop treatment in the middle. This increases risk of resistance, which is more difficult to treat, emphasising the need to treat people with the right drugs and in a timely manner.

“I believe the future of diagnosis is genomics. At the moment, working with Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains requires culturing in an expensive lab set up. By optimising this process, we can ensure this type of work is more accessible to those in countries who are more impacted by infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance. Being able to sequence samples from tuberculosis patients quickly will allow us to tailor treatment if a resistance marker is detected, instead of trying to keep solving the infection with something that is not working, and continuing transmission of the disease. The possibility of applying culture-free sequencing in portable technologies will make this a reality and bring advanced diagnostics closer to the point of care.”

Belén Saavedra,

Postdoctoral Fellow, Parasites and Microbes programme

5. Taking a One Health approach to understand AMR transmission

The Sanger Institute has a long-standing collaboration with the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme (MLW) in Blantyre, Malawi. Here, they conduct a lot of work on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is highly prevalent in Malawi and other low- and middle-income countries.

The Sanger Institute has a long-standing collaboration with the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme (MLW) in Blantyre, Malawi. Here, they conduct a lot of work on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is highly prevalent in Malawi and other low- and middle-income countries.

Dr Patrick Musicha, Head of the Pathogen Dynamics and Antimicrobial Resistance Research Group at MLW, is one of the new International Fellows in Nick’s group at the Sanger Institute. One of his key projects is the Drivers of Resistance in Uganda and Malawi (DRUM) study. This is an extensive piece of work looking at the One Health approach which proposes a holistic approach to designing and implementing interventions for combating the threat of AMR. It considers the interdependence of human, animal and environmental health – One Health compartments. This approach will allow us to understand how water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) practices interact with antimicrobial usage to facilitate the transmission of AMR in Uganda, Malawi and other similar settings.

As part of this study, which has now ended, Patrick and his collaborators collected Escherichia coli isolates from human and animal stools, as well as the environment at five sites in Malawi and Uganda. Samples were sent to the Sanger Institute to generate whole genome sequences and metagenomes – the collection of genetic material recovered directly from environmental samples. While findings are yet to be published, the study underscores the interconnectedness of human, animal and environmental health, and highlights the importance of strengthening WASH infrastructure and systems in such settings.

Sampling from chicken farm (animal) and river (human and environmental) sources for the DRUM study. Image credit: Patrick Musicha.

Alongside his research, Patrick and his colleagues are also working on how to develop a national strategic plan for genomic surveillance. They are trying to highlight the importance of using genomics for routine surveillance, for both AMR and outbreak investigations. These efforts will eventually help highlight the importance of the One Health approach in addressing AMR and the power of using genomics to understand how AMR is spreading in different settings. It will also help to communicate to the relevant stakeholders what are the most effective interventions required to address this problem.

“AMR is a big problem. It's a complex problem but it's not appreciated in the way it needs to be. The reason being is that AMR is not a disease. People don’t realise they are unwell from AMR. When people are diagnosed with an infection, you are mostly likely told you have tuberculosis for example. You won’t really be told you have drug-resistant tuberculosis. This creates a problem in terms of how seriously people want to intervene in addressing AMR, especially when it's circulating in community settings. There is a continued need to raise awareness of the implications of AMR. Alongside this, there is a need to invest in resources to address the problem of access to antibiotics, especially in low-income countries where access remains a big problem. In scenarios where there is access to the commonly available antibiotics and resistance emerges and spreads rapidly, there aren’t alternative options because they are too expensive.”

Patrick Musicha,

International Fellow, Parasites and Microbes programme

6. Understanding AMR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic condition that impairs someone’s ability to clear mucus from their airways, which can lead to the growth and spread of pathogens deep in the lungs. Over 70 per cent of adults diagnosed with cystic fibrosis have a chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, even after intensive treatment with antibiotics.10 Due to frequent antibiotic use, individuals with cystic fibrosis are more susceptible to harbouring resistant strains of P. aeruginosa. A better understanding of AMR in P. aeruginosa in the context of a chronic respiratory infection is key to developing better strategies to detect, treat and reduce antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in these individuals. This will also be important to address infections in other chronic lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which was the third leading cause of death in 2019.11

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic condition that impairs someone’s ability to clear mucus from their airways, which can lead to the growth and spread of pathogens deep in the lungs. Over 70 per cent of adults diagnosed with cystic fibrosis have a chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, even after intensive treatment with antibiotics.10 Due to frequent antibiotic use, individuals with cystic fibrosis are more susceptible to harbouring resistant strains of P. aeruginosa. A better understanding of AMR in P. aeruginosa in the context of a chronic respiratory infection is key to developing better strategies to detect, treat and reduce antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in these individuals. This will also be important to address infections in other chronic lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which was the third leading cause of death in 2019.11

Javier Magide is a PhD Student in Josie’s team at Sanger. As part of his thesis, Javier will be performing bioinformatic and statistical analyses to study the dynamics of P. aureuginosa over the course of chronic infection. With access to a large collection of P. aureuginosa genomes and isolates sampled over time from 200 cystic fibrosis patients, Javier and his team will study 46 of these individuals with chronic infection over six months. The data include sputum samples taken daily over the course of both stable periods and during intensive treatment. This will provide an opportunity to capture the dynamics that lead to AMR in these patients.

Testing antibiotic resistance. Image credit: Javier Magide / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Javier will be exploring the genetic changes that are associated with antibiotics, how long it takes for resistance to arise and degrade with different antibiotics, and how this is affected by other drugs. He will also explore what impact resistance can have on clinical outcomes.

“This is a first of its kind longitudinal study. Previous studies have had much fewer samples following any individual patient. By identifying variants associated with antibiotic use and understanding the evolutionary dynamics of resistance, we can begin to get a clearer picture of how this impacts patients’ clinical outcomes. The hope is that in the future this knowledge will enable us to better detect drug resistance in these patients and predict the response to different treatments, which could influence management and ultimately, improve outcomes for patients living with this lifelong condition.”

Javier Magide,

PhD Student, Parasites and Microbes programme

The team hopes that the insights they gain will not only impact those with cystic fibrosis but also be applied to other similar chronic infections that are an even bigger contributor to global mortality.

7. Navigating carriage of Staphylococcus aureus to address AMR

The CARRIAGE study is an ongoing project that investigates why some people carry the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus in their nose while others never do. S. aureus is a common bacterium found on the skin and in the nose of about one in every three people.12 For most people harbouring the bacteria, it is harmless. However, some people are more susceptible to infections with S. aureus due to a weakened immune system, surgery or a soft tissue injury. In some of these cases, infections can be serious and resistant to antibiotic treatment.

The CARRIAGE study is an ongoing project that investigates why some people carry the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus in their nose while others never do. S. aureus is a common bacterium found on the skin and in the nose of about one in every three people.12 For most people harbouring the bacteria, it is harmless. However, some people are more susceptible to infections with S. aureus due to a weakened immune system, surgery or a soft tissue injury. In some of these cases, infections can be serious and resistant to antibiotic treatment.

Historically, there has been a major focus on S. aureus in hospitals. In the early 2000s, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) caused an epidemic of bloodstream infections – also known as bacteremia or sepsis. In 2003, MRSA infections were at their highest in England with approximately 8,000 people infected – these were mainly hospital acquired.13 This has now fallen to around 900 per year between 2023 and 2024, with 38 per cent being hospital acquired.14 As people in hospital are not well to start with, infection with this bacterium is a major problem. However, the other 62 per cent of MRSA cases between 2023 and 2024 were community acquired and our knowledge of MRSA and S. aureus in general in the community is still limited.

As part of the CARRIAGE project, Katie Bellis, Staff Scientist in Dr Ewan Harrison’s group is hoping to address this gap by understanding S. aureus nasal carriage in the wider community – the nose is where S. aureus commonly likes to live. Some of the main objectives of the project are to understand who carries S. aureus and what lifestyle factors or other bacteria are associated with it, when it does and does not go on to cause disease, and whether there are strains which put you at increased risk of disease.

Katie Bellis at work in her lab. Image credit: Carmen Denman Hume / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The team is using human genome and lifestyle data from blood donors in England, who also agreed to provide three nasal swabs over the course of three weeks to the CARRIAGE study to look at the microbes that live in their nose.

While they are still looking through the data of over 22,000 people, Katie and her team have found that about two per cent of the strains circulating in our community are MRSA, and they are just present in people, not causing a problem. This is a significant difference to the rate of illness caused by MRSA, which was estimated at 1.4 cases per 100,000 people in England in 2018.15 We often think about MRSA in terms of disease, but actually the risk of S. aureus including MRSA, is about it getting somewhere it should not be. By understanding the diversity and carriage frequency of S. aureus strains, we can gain important insights into how infections and resistance develop within the wider community. This in turn will aid in the development of new approaches to detect and treat MRSA.

“Staphylococcus aureus is a part of our natural nasal flora and seen in many animals. So, we would never be able to stamp it out completely. By understanding in detail who carries the bacteria, what strain they carry and what may influence its ability to cause disease, we can then help design new ways to prevent and treat infections, particularly infections that are resistant to first-line therapies. At present, there is quite a lot of interest in vaccination. The hope would be, in the future, rather than necessarily creating a de-colonising vaccine, risking disruption to the microbiome, it would be designed to help prepare your body to mount a good immune response if the bacterium gets somewhere it shouldn't.”

Katie Bellis,

Staff Scientist, Parasites and Microbes programme

8. Tracking Streptococcus pneumoniae after vaccine roll out

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of pneumonia, meningitis and septicaemia worldwide. Although these infections can be treated with antibiotics, those with weakened immune systems, including infants and the elderly, are often more vulnerable to getting seriously ill. In low- and middle-income countries, it is estimated that one million children die of pneumococcal disease each year.16 As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared pneumococcal antimicrobial resistance an important public health concern due to the emergence of strains resistant to multiple antibiotics.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of pneumonia, meningitis and septicaemia worldwide. Although these infections can be treated with antibiotics, those with weakened immune systems, including infants and the elderly, are often more vulnerable to getting seriously ill. In low- and middle-income countries, it is estimated that one million children die of pneumococcal disease each year.16 As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared pneumococcal antimicrobial resistance an important public health concern due to the emergence of strains resistant to multiple antibiotics.

In 2011, in order to address these growing concerns, Professor Stephen Bentley and his group at the Sanger Institute started the Global Pneumococcal Sequencing (GPS) project, which is a worldwide genomic survey of the impact of the pneumococcal vaccine on the bacterial population. Dr Stephanie Lo, Senior Staff Scientist and now lead of this project, is working alongside partners in over 60 countries. They are using whole genome sequencing to explore over 40,000 pneumococcal isolates, determining how these populations evolve to evade the vaccine during rollout.

Alannah King (centre) discussing her research with GPS placement scheme awardees, Rosemol Varghese (left) and Fatima Dakroub (right) from India and Lebanon, respectively. Image credit: Stephanie Lo / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Although the introduction of pneumococcal vaccines has been associated with an overall decline in pneumococcal antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the current vaccines do not target all of the bacterial strains, they just target a subset that cause most of the disease. So far, Stephanie and her colleagues have seen that those strains that are not targeted by the vaccine start to accumulate more antibiotic resistance because they get more exposed to antibiotics after the vaccine roll out. They hope that their continued analyses will be able to guide future vaccine design, and ultimately reduce cases of pneumococcal disease as well as target AMR strains to reduce antibiotic resistance.

One of the team’s key priorities is to enable partners in other countries to do their own analyses. Jolynne Mokaya, Public Health Research and Engagement Lead at Sanger, is leading the delivery of workshops and training to upskill local public health and research scientists on how to do bioinformatic analyses. This in turn can empower the partners to analyse their own data. So far, Jolynne and her colleagues have delivered four workshops in Colombia, India, Gambia and Turkey. For these workshops, the Sanger Institute has donated 10 laptops to the countries to facilitate their analyses.

In the beginning of 2024, GPS launched a placement scheme led by Staff Scientist, Dr Alannah King, supporting low- and middle-income partners from Lebanon, India and Argentina to come to the Institute for three to six months to learn bioinformatics one-on-one and write up a manuscript alongside Stephanie and the rest of the team. With this focused learning, these individuals can then train their colleagues back home to enhance genomic surveillance of priority pathogens in their own country.

In fact, one of their published papers from the first phase of the project supported the roll out of an Indian-made vaccine, Pneumosil, across India. This vaccine was based off circulating serotypes within that country. This paper is part of a growing collection of publications led by GPS partners that includes analyses at the national level with important insights into emerging strains following vaccine implementation.

“Pathogen surveillance is inherently a long-term commitment to improving public health. The GPS project empowers our partners from low- and middle-income countries to conduct longitudinal genomic surveillance within their own countries by providing accessible bioinformatics tools, hands-on training and expertise on the use of cost-effective, emerging technologies.”

Stephanie Lo,

Senior Staff Scientist, Parasites and Microbes programme

9. Investigating how drug resistance spreads across bacteria

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a serious global health problem, but one of the gaps that still exists is in understanding how it evolves and spreads in complex environments. Dr Onalenna Neo, Sanger Excellence Fellow in Nick’s group, is working to close that gap. Her research focuses on trying to understand the dynamics of vectors – mobile pieces of DNA, such as plasmids and transposons, which act like vehicles, carrying antimicrobial resistance genes from one bacterium to another. Ona’s work looks at what vectors we find in certain environments and how this may change over time, including whether it is affected by seasonality. If there is a vector that we know is easily moved between bacteria, and it is present across environments, then we know that there is a risk that this vector may transmit antimicrobial resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a serious global health problem, but one of the gaps that still exists is in understanding how it evolves and spreads in complex environments. Dr Onalenna Neo, Sanger Excellence Fellow in Nick’s group, is working to close that gap. Her research focuses on trying to understand the dynamics of vectors – mobile pieces of DNA, such as plasmids and transposons, which act like vehicles, carrying antimicrobial resistance genes from one bacterium to another. Ona’s work looks at what vectors we find in certain environments and how this may change over time, including whether it is affected by seasonality. If there is a vector that we know is easily moved between bacteria, and it is present across environments, then we know that there is a risk that this vector may transmit antimicrobial resistance.

Ona is presently looking at two complex environments – wastewater from a drainpipe in Addenbrooke’s Hospital and water from the River Cam in Cambridge. Through regular sampling, she is investigating how bacterial communities shift, how resistance genes are spreading, what factors impact their spread and what this could potentially mean for human and environmental health. Over 12 months, Ona will collect monthly samples and use metagenomic analyses to explore which bacteria are present in each environment. To identify which plasmids are linked to which bacteria, Ona will also be growing some of the bacteria in the lab and sequencing their entire genomes using long-read sequencing technology.

Ona sampling water from the River Cam in Cambridge. Image credit: Wellcome Sanger Institute.

These insights could then deepen our understanding of how resistance genes spread through various vectors in different environments, which is essential for assessing risks to human and environmental health as well as for informing the design of effective monitoring, management and mitigation strategies.

“We are working to understand the ins and outs of how vectors carry and spread resistance genes. By focusing on these vectors and tracking their behaviour, we can begin to unravel how resistance evolves and spreads in the wider environment. This understanding is essential if we want to anticipate risks and develop smarter ways to tackle antibiotic resistance before it becomes an even bigger problem.”

Onalenna Neo,

Sanger Excellence Fellow, Parasites and Microbes programme

The team is also developing and refining genomic methods to enhance the efficiency and resolution of these studies. Improving these techniques is essential for accurately detecting and characterising the vectors that may contribute to the spread of resistance.

10. Looking into regional transmission of cholera and patterns of resistance

Cholera is a bacterial disease, caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, usually spread through contaminated water. It causes severe diarrhoea and dehydration. In 2017, the Global Task Force in Cholera Control (GTFCC) published the strategy, ‘Ending Cholera: A Global Roadmap to 2030.’ It aims to reduce cholera deaths by 90 per cent and eliminate cholera in as many as 20 countries by 2030.

Cholera is a bacterial disease, caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, usually spread through contaminated water. It causes severe diarrhoea and dehydration. In 2017, the Global Task Force in Cholera Control (GTFCC) published the strategy, ‘Ending Cholera: A Global Roadmap to 2030.’ It aims to reduce cholera deaths by 90 per cent and eliminate cholera in as many as 20 countries by 2030.

Dr Caroline Cleopatra Chisenga is the Head of Department for the Enteric Disease and Vaccine Research Group at the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia. She is also an International Fellow at the Sanger Institute working within Nick’s group. As part of her International Fellowship, Caroline is assessing regional cholera control within Zambia. Zambia is a landlocked country and shares borders with Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia. As a result, when there is an outbreak of cholera in one of these neighbouring countries, it is likely that the outbreak will spread into Zambia and the other countries more easily. This transmission is the result of several factors including increased travel, trade and floods due to climate change.

Caroline working in the lab, studying cholera transmission and control. Image credit: Wellcome Sanger Institute.

For her project, Caroline will be collecting cholera samples from Malawi, Zimbabwe and Zambia, and sending them to the Sanger Institute for whole genome sequencing. Caroline will be exploring the genetic relatedness of these isolates to understand transmission patterns. She will also be profiling the microbial resistance patterns and picking out which of these are common to all the countries, determining whether this is the result of genetic exchange of resistance genes, or natural change over time.

This is the first time that regional data will be collected for Zambia. At the moment, there is no dedicated funding for surveillance, which is critical moving forward for antimicrobial resistance (AMR). By obtaining this information, we can then inform future measures that need to be put in place in relation to AMR. Without evidence, it would be very difficult to inform policy – data that are specific and unique to Zambia is needed.

I don't think we have reached where we need to be in terms of cholera control and elimination plans. However, I do believe the regional approach that we are taking will generate data that are going to contribute to cholera control. This will hopefully achieve the 2030 set target as well as develop the Multisectoral Cholera Elimination Plan (MCEP), which is going to be a reference document that contributes to combatting and ultimately eliminating cholera outbreaks, particularly in hot spot areas. In addition to this, we also need to educate more people. As people move in and out, information needs to be shared in terms of factors that they need to consider in the environment. Another major challenge that we must address is climate change. I think we can do more in terms of how climate change impacts diarrhoeal diseases, which is something we can start educating communities about.”

Caroline Cleopatra Chisenga,

International Fellow, Parasites and Microbes programme

It is evident from the varied research projects ongoing at the Institute that AMR is not a one solution issue. AMR is a global threat and therefore, needs global solutions. Unfortunately, with current affairs overseas, funding into AMR projects will be impacted. Without these efforts, it is likely that we will go back to a pre-antibiotic era.

While progress has been made in some areas, there are still opportunities to strengthen collective efforts. By working on various microorganisms with partners in different parts of the world, researchers hope to gain a more global view of AMR. AMR does not respect borders, and these new insights will hopefully inform local policies and develop new interventions to help win the war against AMR.

References

- UK Parliament. House of Commons Library. Research Briefing - Antimicrobial resistance. September 2024 [Last accessed: August 2025].

- World Health Organization. World leaders commit to decisive action on antimicrobial resistance. September 2024 [Last accessed: August 2025].

- Antimicrobial resistance: it’s time for global action [Last accessed: August 2025].

- World Health Organization. Fact sheets – Syphilis. May 2024 [Last accessed: August 2025].

- Beale MA, et al. Genomic epidemiology of syphilis in England: a population-based study. The Lancet Microbe 2023; 4: e770–e780. DOI: 1016/S2666-5247(23)00154-4.

- Lieberman Nicole AP, et al. Near-Universal Resistance to Macrolides of Treponema Pallidum in North America. New England Journal of Medicine 2024; 390: 2127–28. DOI: 1056/NEJMc231444.

- World Health Organization – African Region. Yaws (Endemic treponematoses) [Last accessed: August 2025].

- World Health Organization. Fact sheets – Tuberculosis. March 2025 [Last accessed: August 2025].

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report. October 2024 [Last accessed: August 2025].

- Rajan S and Saiman L. Pulmonary infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. Semin Respir Infect 2002; 17: 47–56. DOI: 1053/srin.2002.31690.

- Momtazmanesh S, et al. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. eClinicalMedicine. 2023; 59: 101936. DOI: 1016/j.eclinm.2023.101936.

- Raineri EJM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus populations from the gut and the blood are not distinguished by virulence traits—a critical role of host barrier integrity. 2022; 10: 239. DOI: 1186/s40168-022-01419-4.

- UK. Levels of healthcare-acquired MRSA and C. difficile infections remain stable. December 2013 [Last accessed: August 2025].

- UK Health Security Agency. Annual epidemiological commentary: Gram-negative, MRSA, MSSA bacteraemia and C. difficile infections, up to and including financial year 2023 to 2024. May 2025 [Last accessed: August 2025].

- Public Health England. Laboratory surveillance of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2018. Health Protection Report 2019; 13: 29.

- World Health Organization. Pneumococcal Disease [Last accessed: August 2025].