Image credits: Wellcome Sanger Institute

It has been 25 years since the announcement of the Human Genome Project. We take a look back at the history of the project with some of our long servers at the Sanger Institute, including what it has allowed us to achieve and where it may lead to in the future.

Listen to this blog story:

Listen to "How our beginning is shaping our future: 25 years on from the Human Genome Project" on Spreaker.

On 26 June 2000, former UK Prime Minister, Tony Blair, and former US President, Bill Clinton, announced the completion of the first draft of the human genome. 25 years on and the Wellcome Sanger Institute is still building off the success of this project, propelling genomic research into new areas of health and disease.

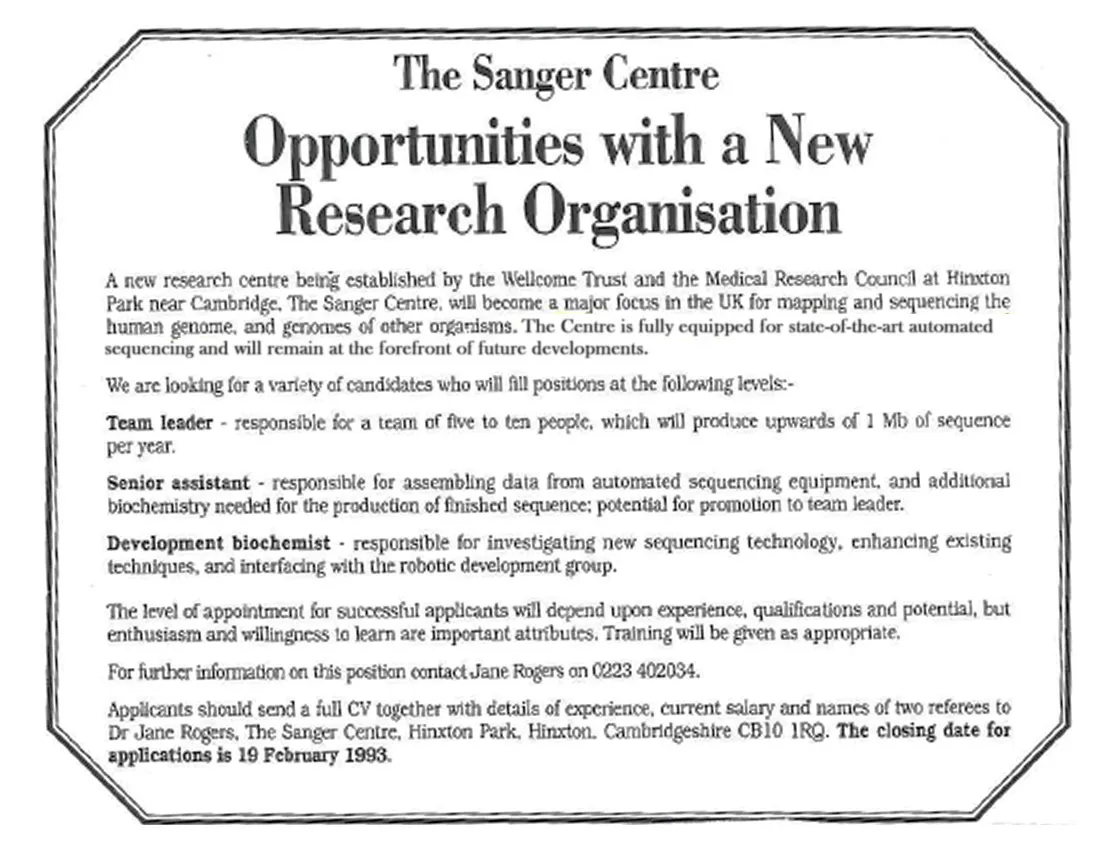

The Sanger Institute, previously known as the Sanger Centre, was established in 1992 to undertake an ambitious project – sequencing the human genome. While the human genome for many scientists is now part of their everyday life, in 1990 when the project was first proposed, the road ahead seemed uncertain. The project was an international collaboration led by John Sulston, Founding Director at Sanger, and Francis Collins, former Director at the National Human Genome Research Institute. In 1998, the so called ‘race’ began when Craig Venter formed a new private company, Celera Genomics, to sequence the genome and make it available only to paying customers. Despite this competition, the race to complete the project fuelled both sides, leading to the work being published two years ahead of schedule. The human genome is now a freely available resource for scientists all around the world.

“For let us be in no doubt about what we are witnessing today – a revolution in medical science whose implications far surpass even the discovery of antibiotics, the first great technological triumph of the 21st century. And every so often in the history of human endeavour there comes a breakthrough that takes humankind across a frontier and into a new era. And like President Clinton, I believe that today's announcement is such a breakthrough – a breakthrough that opens the way for massive advances in the treatment of cancer and hereditary diseases, and that is only the beginning.”

Former Prime Minister, Tony Blair,

during the June 2000 White House Event

Since this monumental achievement, the impacts across science, medicine and society have been profound. The project has led to advancements that have brought us closer to the development of personalised medicine and improved our ability to diagnose. For example, the project has led to the identification of disease-causing genes for many rare disease patients as part of the Deciphering Developmental Disorder (DDD) study. In addition, the project has accelerated research in genetics, uncovering new genes and pathways involved in health and disease. Alongside the improved knowledge, technologies to sequence and edit the genome have developed. For example, in 2001, sequencing the human genome took 13 years at a cost of $2.7 billion US dollars. Now, reading the equivalent of a single gold standard (30x) human genome takes roughly 11.8 minutes and at a cost of a few hundred pounds. This rapid improvement in cost and time has revolutionised our ability to study multiple genomes at the same time – from both humans and across life on Earth. Our teams are also capitalising on technological advancements to map all of the cell types of the human body, as part of the Human Cell Atlas, which has the potential to help with diagnosing, monitoring and treating disease in the future.

Another benefit we have seen from the Human Genome Project is the power of international collaboration and access to data – something which is still an important part of our culture at Sanger today. We currently have many ongoing collaborative projects at the Institute, including the Cancer Dependency Map, Darwin Tree of Life and the Global Pneumococcal Sequencing Project. All of these projects are using expertise from around the world alongside next-generation technologies to improve insights that will impact communities globally.

Although the original human genome reference was a mosaic of the genomes of people with primarily European and African descent, over the last 25 years, our understanding of genetic diversity has improved dramatically. We have learned the value of sequencing different populations to address health disparities and get a clearer idea of disease and treatment response across individuals. For example, Project Jaguar is an ongoing project between Sanger and seven Latin American countries to explore how genetic diversity shapes immune responses across the region.

The lessons learned from the Human Genome Project do not just impact humans, they also have implications for all life on Earth as well as our climate. For example, genomic surveillance was critical in our fight against COVID-19 and will be vital in predicting the next pandemic. In addition, researchers are using genomic surveillance to track how our climate is impacting disease in Bangladesh, in a recent collaboration with icddb,r. Our teams are also contributing to several global collaborations to sequence reference genomes of species around the world – from flying insects to flying eagles, these genomes will be vital in conservation efforts as well as changing the way we do fundamental biology.

The most recent impact of the Human Genome Project can be seen in advancements across artificial intelligence (AI) tools and synthetic biology. The combination of these tools will accelerate and scale-up research. They will enable the analysis of complex genomic datasets, identification of hidden patterns that cannot be done by humans and generation of large outputs that will enhance discovery and healthcare opportunities.

The impact of the Human Genome Project can be seen across all genomic research. With these foundations, the genomics community can continue to break boundaries and tackle ongoing health issues around the world.

In this blog, we caught up with some of our staff who were at the Sanger Institute from the beginning to understand what it was like at the start of this voyage, what we have learned and where we may be heading over the next 25 years.

- Matthew Jones, Staff Scientist, Sample Preparation

- Suzanne Szluha, Inventory and Logistics Coordinator, Stores

- Tracey-Jane Chillingworth, Advanced Research Assistant, Long Read Team

What did you expect when the beginning of the Human Genome Project was announced?

Suzanne: I had no science background and applied for a job as a Purchasing Assistant. My background was in finance, and I previously worked at a light aircraft maintenance company – so I had no knowledge of what the Human Genome Project was or expectations as to what it would achieve. This was a totally new area for me but from my first day, it was apparent that it was something big!

Matt: At the time, I was aware of suggestions that the Human Genome Project should take place. During my postdoc, I had been involved in sequencing a DNA virus of rice and genes involved in making haem – a molecule used for various processes like photosynthesis – in the blue-green algae, cyanobacterium. Even with this limited experience of DNA sequencing, I still knew that the Human Genome Project was going to be a huge undertaking. It took me a little while to understand how this massive project was actually going to be achieved.

Tracey: When I first started, I was in the pathogen team working on other projects. We didn’t know what to expect when this was announced. Although we knew it was going to be a big project, it was unknown whether it could be done, what the challenges were going to be, how long it would take and also how it would change science.

What was it like during this period at the Sanger Institute?

Suzanne: I really enjoyed working here at the beginning of this adventure, and this is still true today, it had an amazing, big family feel. I was setting up the Stores facility in my early days at the Institute and when workload required another member of staff, I would step in to help. Although there were leaders, it was clear that no one was more important than anyone else. I remember clearly John Sulston standing in the queue at the Stores counter when needing plates or tubes for his work! There were always lots of celebrations when milestones were reached. It was a very inclusive and positive atmosphere.

Matt: I joined the then Sanger Centre in April 1993. At this time, the cosmid mapping and subcloning parts of the process were continuing at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) in Cambridge, mainly because we were not able to undertake radioactive work at Sanger. Subcloning was used to cut smaller pieces of DNA out and insert them into smaller vectors, such as cosmids, for analysing. Cosmid mapping is a technique used to locate where genes are on a chromosome using special DNA carriers called cosmids. Cosmids are a hybrid of a plasmid – small circular DNA – and lambda phase DNA – a virus that infects bacteria.

So, I began my time at Sanger at the old LMB labs on the Addenbrooke’s site. My first lab book from that time was lost and my subsequent lab books went to the Wellcome Trust archive, but I am fairly confident that the initial work I undertook was subcloning some overlapping cosmids covering part of the rhodopsin gene on human chromosome 3, which is important for vision.

When I moved to the Hinxton site, our labs were on the first floor at the northwest corner where the first sequencing machines were. Just along the corridor it was possible to look down into the ‘fishbowl’, named due to the visibility of work going on below, where a number of sequencing groups were located. I was mostly subcloning cosmids and fosmids – similar to cosmids, but based on the bacterial F-plasmid – for the Caenorhabditis elegans and yeast projects. We moved onto P1-derived artificial chromosomes (PACs) and bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) later in the projects. Both of these genetic techniques are used to clone and study large fragments of DNA.

There was a lot of work to do, but it never felt overwhelming. I really enjoyed the working environment and the location.

Tracey: It was exciting as we had regular updates on how many chromosomes had been mapped as they were split up and done by different teams. We stopped our pathogen-related projects to help out too.

There was a sense of pride to make sure that what we were putting out there was correct, and that the data were free to be used by all. We were also up against Craig Venter and his team so there was a bit of rivalry.

Since its completion, what has the Human Genome Project allowed us to do, and what have we learned?

Suzanne: Although I am not a scientist, I can see that mapping the human genome has enabled huge advances in understanding genetics and diseases – and making it available to all was an important part of this.

Matt: I think others might have a better understanding of the scientific impacts. However, for me, the main lessons are that it is possible to cooperate internationally to achieve a common objective and that the principles of free data release are essential for those collaborations to succeed.

Tracey: Being able to map the human genome has brought amazing discoveries in medicine. It has allowed us to identify and map disease-related genes, like BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are linked to breast cancer, and then go on to find new medicines to treat these. It has also allowed us to uncover viruses and illnesses that we previously were not sure about. Children can now have their DNA sequenced to identify unknown illnesses to allow quicker diagnoses and treatment.

Alongside this, it has been important to make sure that the human genome is being used in an ethical way and for good, and this can at times, still be a controversial topic.

The human body is an amazing and complex structure – sequencing the genome has, and will continue to, allow us to unravel some of this fascinating complexity.

What will the Human Genome Project enable us to do in the future?

Suzanne: Again, although I am not a scientist, I think it will continue to improve so many areas of health in a way that would not be possible without the results from the Human Genome Project.

Matt: I am sure that there have been, and will continue to be, contributions from the data generated by the Human Genome Project for advances in medicine and understanding of human health. But I feel that the most significant result of the project is the firm foundation for future collaborative working between laboratories internationally to further our understanding of biological science.

Tracey: I think the Human Genome Project will continue to transform the NHS. It will hopefully enable us to develop and prescribe the right treatments for patients as well as identify and eradicate infectious diseases around the world.

Outside of healthcare, I think it will help develop and manipulate genes to assist in food production and greater yields to support in ending food poverty.

We live in a different world now compared to when the Institute was first established – but our values have not changed. International collaboration and open sharing of data were foundational to the Human Genome Project and continue to drive a lot of our research today. The legacy of the Human Genome Project can still be seen across research and in people’s enthusiasm to push the boundaries and explore new ways to deepen our understanding of health and disease. With new advancements such as AI transforming our work, it is amazing to reflect back on how far we have come. Just as the Human Genome Project started as an idea, the next 25 years will be full of new ones with different journeys that will continue to transform the world around us.

“The 25 years since the announcement of the completion of the human genome has transformed our understanding of biology in both predicted and unpredicted ways, from the origins of our species, to how genomes operate as a blueprint for life, to the genetic underpinnings of disease, to the routine medical use of whole genome sequencing.

“Advances in DNA sequencing technologies have democratised a technology previously only available to a few, opening up the prospect of sequencing the genomes of all species on our planet. Discovering how life has evolved over billions of years and the diverse solutions life has devised to overcoming the challenges it has faced, and what this might tell us about solving the challenges we now face as a species, is but one of the exciting prospects for the next 25 years.”

Professor Matt Hurles,

Director at the Wellcome Sanger Institute