Image credit: Adobestock

This month we are celebrating a new milestone of sequencing 50 Petabases of DNA. Large-scale sequencing projects have contributed to this achievement, providing us with unprecedented insights into human health and disease.

Listen to this blog:

Listen to "A melody of bases How scaling allows us to set new bars" on Spreaker.

Every learning process has a beginning. A moment where you are unsure of whether you will achieve your goal and a moment of doubt. In music, most new learners start with scales — a series of notes that form the foundation of music and allow composers to build new melodies and harmonies.

At the Wellcome Sanger Institute, our beginning was in 1993 with the goal to sequence the human genome. A feat that was deemed impossible by both scientists and non-scientists around the world. Flash forward to 2024 and the impossible has happened — no not Oasis getting back together — but the human genome has already been sequenced and the Institute has now reached an exciting new milestone of sequencing 50 Petabases (Pb) of DNA.

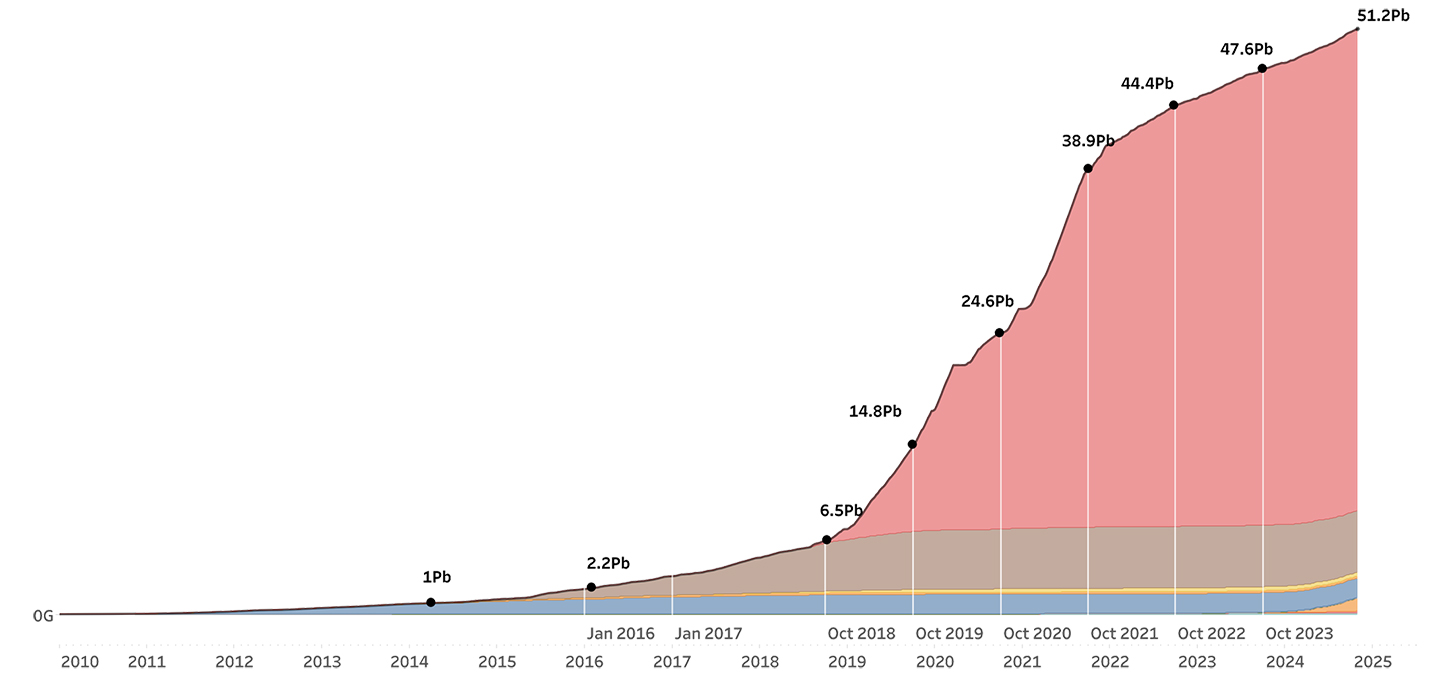

Sanger Institute's DNA sequencing over time

50 Pb is fifty thousand trillion bases of DNA, which is the equivalent of sequencing over half a million gold-standard* human genomes. Whilst this may seem like just a fancy number, we can learn a great deal from these sequences of bases. They can allow us to form the foundation of our understanding and build new possibilities for human health and disease. By continuing to scale up our projects, we can gain deeper insights and set ourselves new ‘impossible’ bars. It can always seem daunting at the beginning — but it is something we here at Sanger know how to do best.

So, how did we get here? What have we achieved? Where are we going? Well, let us go back to the very beginning; we have heard that is a very good place to start…

A crescendo: Increasing our ability to sequence human genomes

When we first started sequencing in 1993, the sequence of bases being produced could fit on a scrolling ticker which was placed in the reception area for all to see. Now, the Institute has sequenced over 51 million bases for each second of Sanger’s history.

dna_letters_ticker

Ticker in the Sanger Institute's Sulston Building, showing the letters of DNA being processed. Image credit: Wellcome Sanger Institute

The Sanger Centre, now known as the Wellcome Sanger Institute, was set up with the purpose of sequencing the human genome and ensuring its free accessibility to researchers. The first draft of the genome became available in 2000 and was later finished in 2003 (99.999 per cent complete) using hierarchical shotgun sequencing. This approach involves creating a map using large, ordered fragments of DNA. These fragments are then broken into smaller pieces, sequenced and computationally reassembled on the basis of overlapping sequences.

The Human Genome Project revealed that humans have 20,000 genes rather than the 100,000 previously estimated. This project not only continues to act as a fundamental resource for improving medicine and accelerating our understanding of human biology, but it has also increased our awareness of the value of data sharing and encouraged the development of new technologies. Today, a single human genome is being sequenced every 12.1 minutes at a cost of only a few hundred pounds.

Despite this great achievement, most of the original reference genome (70 per cent) came from one individual of mixed descent, with the remaining 30 per cent from a combination of 19 other individuals of mostly European descent1. In order to gain a deeper understanding of common human genetic variation across a more diverse population, the 1000 Genomes Project was launched in 2008. This project optimised the use of next-generation sequencing technologies to understand genetic variation across different ethnic groups at a resolution that was unmatched by other resources. Finishing in 2015, the project actually sequenced more than 2,500 genomes, instead of the original 1,000 that was planned, and provided key insights into genetic differences that make us all unique and can potentially lead to disease.

Watch Wellcome's video about the 1000 Genomes project

On the 10th anniversary of the completion of the first draft of the human genome, another new daring project was launched — the UK10K Project. This project aimed to build on the insights from the 1000 Genomes Project by uncovering disease-causing variants from 10,000 human genomes. There were two main components to this project to help identify rare variants and their effects. The first included the genomes of 4,000 people with well-documented physical characteristics to identify if genetic changes could be linked to disease. The second involved studying the changes within protein-coding regions of DNA (areas that tell the body how to make proteins) of 6,000 people with extreme health conditions. These were compared with the first group to help identify how the changes were responsible for particular health conditions.

uk10k_logo

Logo of the UK10K project

The project, which ran from 2010 to 2013, allowed researchers to understand how genetic variation could contribute to people’s traits as well as disease on a large scale. This project also paved the way for the 100,000 Genomes Project, managed by Genomics England, which sequenced the genomes from around 85,000 NHS patients affected by rare diseases or cancer. This groundbreaking project has illustrated the power of genomics in healthcare and created one of the largest genomic health data resources in the world. Researchers at the Sanger Institute have already utilised this resource in their work, including a recent study that identified multiple genes linked to the timing of menopause as well as to cancer risk. This emphasises the importance of data sharing and open accessibility to progress our collective understanding.

More recently, the Sanger Institute was involved in sequencing the genomes of the UK Biobank participants. The UK Biobank is a large-scale biomedical database and research resource that contains in-depth genetic and health-related information from half a million UK participants. In 2019, the Institute was employed, alongside deCODE in Iceland, to sequence the whole genomes of the 500,000 UK Biobank volunteers. In just over three years, the Sanger Institute sequenced 243,633 whole human genomes. This dataset, which is accessible to vetted researchers, is a powerful resource that is already providing insights into cancer, diabetes and heart disease.

From that initial goal of a single human genome, the Sanger Institute has since been involved in sequencing whole genomes en masse. This scale has allowed us to go from simply understanding where all the genes are in the genome to delving deeper into genetic variation and how this can impact human health and increasingly, all life on Earth.

An ensemble: Studying microorganisms to gain insights into human diseases

Large-scale sequencing does not just apply to humans; sequencing the genomes of other animals and microorganisms is vital in understanding more about human health as well as the environment we live in.

The Sanger Institute has been at the forefront of sequencing and discovering more about major microorganisms that cause disease. In 1998, Sanger was involved in sequencing the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis — the bacteria known to cause the infectious disease tuberculosis. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, tuberculosis has returned as the leading cause of death from a single infectious disease worldwide 2. In 2023, a total of 1.25 million people died from tuberculosis, mostly individuals living in low- and middle-income countries2. Sequencing of the M. tuberculosis genome identified 4,000 genes, which has helped us better understand the transmission and resistance of bacterial strains.

But how can sequencing microorganisms provide benefits to human health? This can be nicely demonstrated by the work done at Sanger on MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus). MRSA is a group of bacteria that are genetically distinct from other strains of S. aureus due to their resistance to the majority of antibiotics. Although the number of cases of MRSA in the UK has been decreasing over time, the rates have remained relatively constant over the past four years (1.4–1.5 per 100,000 population)3. MRSA is difficult to treat and thus, can have life-threatening consequences.

In 2004, the team at Sanger and colleagues sequenced the genome of an MRSA strain, revealing several unique genetic elements related to its virulence and drug resistance. The genome sequence was also able to provide evidence of the movement of DNA between organisms, which ultimately allows the bacterium to evade human defence mechanisms.

The value of this information was demonstrated on a wider scale in 2012 when researchers from Sanger and collaborators used sequencing technologies to confirm the presence of an MRSA outbreak in real time. The researchers analysed MRSA samples from 12 patients who were carrying MRSA. Using DNA sequencing technologies, the team were able to demonstrate that the samples of MRSA were closely related; thereby, confirming the presence of an outbreak.

Our video explaining how we used sequencing to stop an MRSA outbreak

During the sequencing process, the team identified a new case of MRSA in a different hospital unit and used sequencing to demonstrate that this strain was also part of the outbreak. This resulted in the team sequencing 154 healthcare workers for MRSA and consequently identifying one staff member who was unknowingly carrying and transmitting MRSA. In this case, the sequencing of MRSA genomes was applied to control an outbreak in real time, preventing further risk to patients and potentially saving lives.

The experience gained from this and other research was also fundamental to the large-scale sequencing operation that took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, as the world went into lockdown, the Sanger Institute jumped into action to provide a centralised service for large-scale genome sequencing of COVID-19 samples from across the UK. The team sequenced 2,365,291 coronavirus genomes which helped to identify and track the impact of circulating variants as they appeared as well as assist in vaccine development. Genomic surveillance on such a scale allowed the team to work closely with public health authorities to guide their responses in real time.

How we used sequencing to monitor COVID-19

These cases emphasise that whilst sequencing one singular microorganism genome can provide us with valuable insights, harnessing the power of thousands can provide even greater value that can influence public health and ultimately, save lives.

A chord: Pulling together single-cell and spatial data

Sequencing whole genomes can provide us with a better understanding of genetic variation; however, identifying the impact of this on a finer scale is important. With the latest advancements in single-cell sequencing† and spatial genomics‡, we are now able to uncover more about human development and disease processes by exploring our cells at the molecular level.

For example, the Human Heart Atlas, part of the Human Cell Atlas, aims to enhance our understanding of heart health and disease, which could ultimately guide personalised heart medicines.

A 2020 study published by the Sanger Institute and collaborators utilised single-cell technology, machine learning and imaging techniques on nearly 500,000 individual cells and cell nuclei from six different regions of healthy hearts. The researchers were able to identify exactly which genes were switched on in each cell, discovering major differences in the cells in different areas of the heart. By understanding gene activity across the range of heart cells, researchers will hopefully be able to understand heart function and how this is ultimately impacted in disease.

Last year, the team went one step further by producing the most detailed and comprehensive human Heart Cell Atlas to date. For the first time, they described the characteristics of the cells that make the heart beat. By using spatial transcriptomics, the researchers were able to uncover a ‘map’ of where the cells sit within a tissue and how they can communicate with each other. These findings have the potential to be instrumental in understanding more about diseases that affect heart rhythm.

Move the slider to see the heart tissue slide and the functional areas annotated by Prof. S. Yen Ho. The sinoatrial node is in red.

Move the slider to see the two different zones within the heart's sinoatrial node - central and peripheral - revealed by spatial genomics conducted by Kazumasa Kanemaru.

Advances in genomic technologies have allowed us to look more closely into the 37 trillion cells in the human body. This in turn has meant we can begin to classify what each cell does and how it works. By going a little deeper, we can also begin to explore how these cells interact with each other at tissue and organ levels. This will be necessary to gain a more comprehensive picture of human biology as well as highlight where things can go wrong in disease and potentially identify new ways to prevent or treat this.

Celebrating our range

On Tuesday 5 November 2024, the team at the Wellcome Sanger Institute marked the 50 Pb milestone with celebrations. With cake in hand, the team looked back at how technological advancements, innovation, international collaboration and forward thinking have contributed to this achievement. Over the past 30 years, the Institute has been a leader of genomic research, providing insights that have deepened our knowledge of biology, medicine and life on earth. The six dedicated research programmes at the Institute are continuing to push boundaries to reveal more about human, pathogen and cellular life.

Most importantly, by designing our experiments at a scale only few can achieve, we are placed in a unique position to continue generating large amounts of data. These data combined with new technologies can then be used as new instruments by researchers at Sanger and around the world to amplify, explore and interpret the power of genomics. This is opening up a new era in science. One which will see the tempo of discovery accelerate.

50PBCake

Celebrating with cake. Image credit: Shannon Gunn / Wellcome Sanger Institute

*A gold-standard 30x genome is a genome where each base has been sequenced an average of 30 times.

†Single-cell sequencing comprises a series of methods used to isolate and analyse sequence information from individual cells.

‡Spatial genomics is the study of the genomic information of single cells within their native tissue environment.

Find out more

- Learn more about our six research programmes

- Take a look back at our previous 10 Petabase milestone and the technology use to deliver it

References

- NIH National Human Genome Research Institute. Human Genome Project. Available at: https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/educational-resources/fact-sheets/human-genome-project [Last accessed: November 2024].

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis. October 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis [Last accessed: November 2024].

- NICE CKS. MRSA in primary care: How common is it?. January 2024. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/mrsa-in-primary-care/background-information/prevalence/ [Last accessed: November 2024].